Analysis

This hearing was part of the dispute over the succession to the Swyncombe Estate in Oxfordshire (see also [2015] WTLR 1165, [2015] EWHC 752 (Ch)). This hearing concerned three applications by Stephen Christie-Miller (Stephen) to re-plead his case.

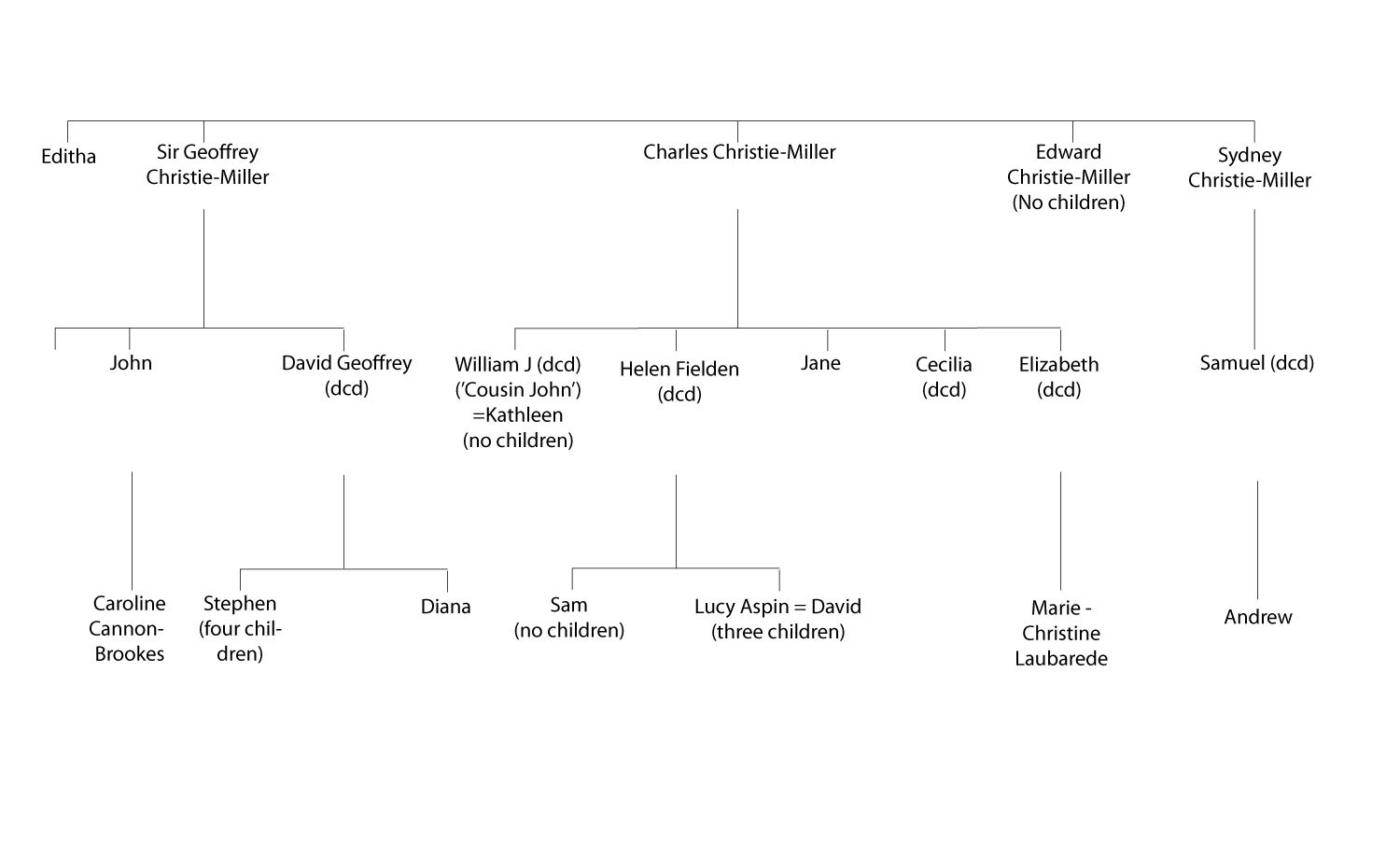

The estate, which consists of land in and Swyncombe, is in two parts. One part is held upon the trusts of a settlement dated 18 February 1976 (the settlement) executed by Charles Wakefield Christie-Miller (Charles). The other part is held upon the trusts declared by the will of Charles’ son, William John Christie-Miller dated 15 March 1998 (the will trusts). Samuel John Fielden (Sam) is the grandson of Charles, and Stephen Christie-Miller is the son of David Christie-Miller, the nephew of Charles. The class of discretionary beneficiaries under the will trusts and the settlement included both Stephen and Sam. In early 2005 the settlement trustees resolved to grant Sam interests in the settlement. In March 2007, the will trustees purported to exercise the testamentary power of appointment in favour of Sam absolutely. The terms of the deed became controversial, and resulted in Sam launching proceedings against Stephen and the former and current trustees of the will trusts, seeking declaratory relief as to the construction of the deed, or alternatively, rectification of it. Stephen brings a counterclaim and part 20 claim, seeking declaratory and other relief to give effect to what he contends is the correct construction of the deed. He also asserts an interest in a certain farmhouse on the basis of proprietary estoppel.

Following an earlier hearing, Stephen had produced an amended defence to Sam’s claim, and a re-pleaded part 20 claim (the revised pleading). This introduced two wholly new claims. The first (the rectification claim) was on the basis that the will would be subject a claim for rectification under s20 AJA 1982 on the basis that John executed the wrong will. It was asserted that the will he had intended to execute contained a narrower class of discretionary beneficiaries that did not include Sam. It was further asserted that the will and settlement trustees were aware of this mistake and had failed to take it into account when exercising their discretion. Stephen’s revised pleadings did not themselves seek rectification, but simply stated that Stephen intended to apply for permission to bring separate proceedings for rectification (permission would be needed as the rectification claim was more than 15 years out of time). However, in a separate application Stephen had applied for permission under s20(2) AJA 1982 to bring the rectification claim. In a third application he had sought permission to use materials disclosed in the present proceedings in the proposed rectification proceedings.

The second new claim (the trustee removal claim) is for the removal of the settlement trustees and the appointment of others in their place, based upon an alleged lack of neutrality in their conduct of this dispute.

Held:

-

- 1) The relevant test for permission to amend was that the claim must have a real prospect of success. Stephen had failed to demonstrate that he has a real prospect of proving at trial that John executed the wrong engrossment. The revised pleading would not be permitted to include the rectification claim or any reference to it.

- 2) Permission to bring the rectification claim out of time and the application relating to use of materials in the rectification claim was refused for the same reasons.

- 3) (obiter) if the judge had concluded that the rectification claim had a real prospect of success he would not have refused permission to bring the separate proceedings on the grounds of delay or prejudice.

- 4) The entire Trustee Removal claim was disallowed. The Part 20 claim against the settlement trustees was plainly hostile litigation to which the trustees were entitled to plead. The trustees might have been open to criticism if, believing the claim to be without merit, they had stood by and done nothing.

- 5) An objection to the trustees acting by the same solicitors and counsel was similarly rejected. The trustees unanimously denied that any representations (relevant to the alleged estoppel) were made to Stephen, so it could not be said there was a conflict between the four trustees such as to warrant separate legal representation.

- 6) The settlement trustees were entitled to the costs of the earlier successful strike-out application.

- 7) Prima facie, Stephen was required to pay the costs of two earlier applications for permission to amend. Stephen was also required to pay all of the costs of the latest application and thus of the hearing as a whole.

Continue reading "Fielden v Christie-Miller & ors [2015] EWHC 2940 (Ch)"